Many songs have been sung and stories written about the city of Harbin, and this city has gone through many extraordinary times. The builders provided its foundations; after them came the conquerors, then the liberators, later the nationalists and lastly in 1949 its landlords, the Chinese, under the leadership of Chairman Mao. This is a basic introduction; details about who dug up the earth, chopped the wood, laid the bricks and sewed the attire are left at the edges of my story, as I will be looking at those who gave medical treatment to the people of Harbin.

For instance, five Russian doctors died helping patients during the plague epidemic at the start of the twentieth century. These were the pioneers, finding themselves in the faraway region of Manchuria for various reasons. Without digressing, I want to tell you about one Harbin servant of many years who would alleviate the pain of the city’s inhabitants and whose fate would become intertwined with mine. This is the story of Harbin’s Central Railway Hospital’s first dentist.

Maxim Yakovlevich Netrebenko was born in the village of Petrovka in central Ukraine. His father was a free agriculturalist, having gained his freedom by decree of Tsar Alexander I. Maxim spent his childhood in Kiev, working at his uncle’s forge, and at twenty-one he was called up for military service. This was in 1901.

It all started in the village of Baranovichi, where the military headquarters of Tsar Nicholas I were located. New recruit Maxim was enlisted in the 3rd Medical Railway Battalion, and while a song about the Varyag cruiser hadn’t been composed yet, trouble was already brewing in the East with the Japanese seizing China’s Liaodong Peninsula, the site of the future fortress of Port Arthur. Maxim and his comrades in the battalion began to receive their instruction in military medical aid, and this

is when the young medical orderly’s talent for extracting bad teeth was discovered. There was plenty of work, as there was no other way at the time in Russia to help those in pain from bad teeth.

Three and a half months later they heard that there would be an order to cast off, only no one knew where to. And when people suddenly started to whisper one dull morning in autumn that they were going to the East, many didn’t understand how far and why they were going.

The hospital train set out, consisting of four carriages fitted out with equipment. The dental department, as it was called, took up part of the first carriage, where Doctor Alshansky’s office was located. Along with a small range of instruments, the dental department had a solid oak armchair and two imposing anaesthetists, who were also present during other medical operations requiring anaesthesia. This military hospital train set out and in 1905 with millions of stops, long periods of standing, regroupings and constant exercises and training sessions arrived at the Chenggaozi railway station, thirty kilometres from Harbin. By this time Maxim Yakovlevich now already had his military medical assistant certificate and had had thousands of thankful patients relieved of their pain.

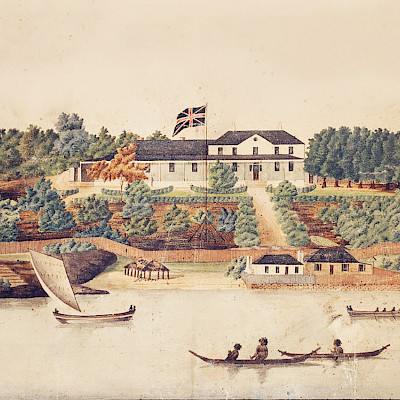

The war with Japan had come to an end, but the flow of the wounded and the maimed kept on streaming into Harbin. An order was received to make hospital wards in adobe structures bought from local peasants, and these same peasants were offered jobs in constructing the hospital. The period of military service was complete for most of the soldiers who had come with the railway battalion, and they could be “dismissed” of their own accord to leave for wherever they liked.

Doctor Alshansky, an already long since retired veteran, was called to the Central Railway Hospital in Harbin to head one of the departments, but he returned to Chenggaozi on a Chinese droshky a few days later and, once he had found Maxim Yakovlevich, begged him to help him at the hospital.

Thus began a new stage of the young man’s life. He sent for some instruments and books from Germany and worked twelve hours a day, six days a week.

In 1907 Madame von Arnold, who had arrived from Germany, opened a dental school after inviting Maxim Yakovlevich to teach there. While working with her, he also (paradoxically) officially received a diploma from the school. Vladimir Opadchy, who also found himself in Australia in 1957, would later graduate from the school and receive the title of dentist.

On one of the hospital’s visiting days in 1907, Maxim Yakovlevich got into a conversation with his patient, who turned out to have originally come from the same region that he himself was from. It turned out that his new friend had come to Manchuria in a group from as far back as the time of the pioneers and now occupied an influential post in the supply department for railway under construction. He told how he wanted to start his own business and was close to fulfilling his ambition, but he didn’t have enough money. Always ready to help, Maxim Yakovlevich acquaints Mr Zaiko with Harbin Russian millionaire I. Chistyakov — the king of Chinese tea — and shortly afterwards the sausage factory Zaiko & Co. started up in town. At that point a friendship between two families lasting more than a hundred years began, and their descendants met again in Harbin on 15 May 2009 at the theatre in the Moderne for the first Russian ball since the exodus and worldwide dispersion of inhabitants of the city of Harbin.

In 1916 Maxim Yakovlevich Netrebenko took a leave of long duration and returned to Russia, where after twelve months of concentrated study he passed his examinations at Tomsk State University and received his graduation certificate with a certificate of merit.

Afterwards it was his home village, Kiev and travels along the shores of the Black Sea, where in the then small town of Sochi he acquired a plot of land for building a house with the hope of opening a dental surgery; the titles have remained intact to this day! But fate had other ideas, and in 1917 he returns to Harbin and continues working as a dentist at the hospital until 1924. After building his house in Novy Gorod on Glukhaya Street, not far from the railway administration, he opens his dental surgery, the equipment for which he had brought from Germany in 1917 already. He was at this job until he departed for Australia in 1957.

At the request of the Chinese department of health, tens of young Chinese medical students did

their practical work at his surgery. Maxim Yakovlevich Netrebenko spent half a century in Harbin as a dentist.

Written from my father’s memoirs and those of my own

Constantine NETREBENKO

Translated by Samuel Brotchie

Translator’s note

This translation is a translation of the original text and was completed by me in 2020 during my bachelor honours degree programme in the field of Russian.

I am not a professional translator and have no formal translation qualifications. Any mistakes in this translation should be considered in this context. Any views expressed in this translation are not a reflection of my views.

If any text in this translation contains text from external sources, this is indicated in this translation, and the details of these sources can be found in a list at the end of this translation.

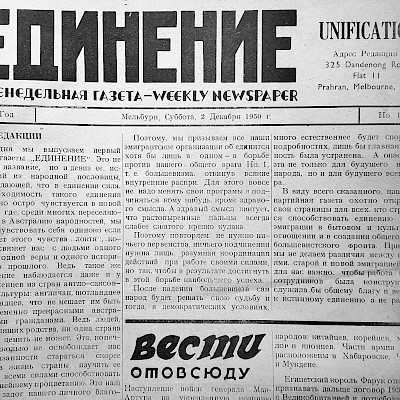

I feel privileged to have had the opportunity to produce this translation, and I hope that it is of benefit to the literature on Harbin Russians and to the Unification community.

Samuel Brotchie

February 2021