An essay on Russian Harbin

The capital of the imperial dispersion in the East, Harbin remains in the memories of many as the Kitezh of the 20th century, a Russian Atlantis gone beneath the waters of history. It was called “a bright candle on distant foreign banks” by Alexander Vertinsky. Half a century ago marked the end of the brief but so memorable existence of this unique enclave that for half a century had preserved in exile the traditions and culture of pre-revolutionary Russia. Departing via the Otpor border station deep into the USSR were the last carriages of Russian people returning to the homeland who after the revolution and civil war had found refuge in north China.

A presentiment of the USSR

“Look, Mikhail, over there, it seems, ravens are flying! Small creatures! So we won’t be done for, if anything crops up, we’ll be hunting!”

My neighbour Ivan Kuznetsov, a guy of heroic stature and incredible strength, ran across at the station from his carriage into ours, and now he and father are sitting facing one another by the window and not all that cheerfully making jokes. The fifth or sixth day passes since we crossed the border and have been travelling in Soviet land. We don’t get bored of looking: everything is new and never before seen. Lake Baikal is left behind us. At the main stations, we’re provided with boiling water and soldier’s soup. Siberia goes on and doesn’t stop at all. We have no idea where we’re being taken to, where the stop is at which we’ll have to get off and begin to live anew. We had got ready to go to the Union, but what’s there and what it’s like there—even the grown-ups themselves, like we children, who are guessing, don’t know much more than us.

“Now, Ivan, you’ll be seeing meat only on Soviet public holidays,” says father. “There probably aren’t shops at all.”

“Then whatever is the money for? No, if money is being printed, then there has to be selling of some kind too.”

“Oh, well, do you remember people were saying that communists live without money? Now I see that they were talking nonsense.”

Kuznetsov takes the brand new notes out of his pocket and examines them closely, “Just look, with Lenin!” “Get used to it!”

At the border station with the harsh name of “Otpor”[1] (it was later renamed “Druzhba”[2]), we were given “relocation expenses,” a sum of Soviet money for the time being. But then they took away everything that was “illicit”—icons, books and gramophone records. It grieves me to the point of weeping, the old Bible with Father Alexei’s blessing. At the same time, a gift for our grandfather from Tsar Nicholas was lost too: father was afraid of taking a book by the engineer Gerasimov about the ores of Zabaykalsky Krai because of the tsar’s signature and burned it himself back home like many other things too—photographs, books and things that could have, in his opinion, caused trouble.

At the border, the special trains would be met by the manpower “buyers,” as they were known, from the virgin land farms of Siberia and Kazakhstan. They would go along the special train, look into the carriages and begin to talk; they would pick out workers who were stronger and younger. Our carriage, among ten others, was acquired by the Glubokinsky sovkhoz in Kurgan Oblast. We were set down at Shumikha station and taken on little smashed-up trucks to a region that was such a backwoods that even now, half a century later, isn’t easy to get to because of the lack of roads.

Gone with the storm

The maelstrom of the civil war and the Great Russian[3] Exodus were like a tale to me as a child, somewhat scary but fascinating too, beckoning, just like all stories grandmothers tell. Dust being raised about the Transbaikal settlement of Borzya by Ungern’s detachment—dusty, savage, hairy horsemen. The baron himself, in a black burka[4] and white papakha on a black horse, threatening someone with a tashur[5], a thick Mongolian whip. The endless strings of carts with refugees and the artillery of the advancing “comrades” thundering after them. At that time, my grandfather Kirik Mikhailovich too made up his mind to get across za rechku (“the other side of the small river”), as people said, across the Argun, with his family to pass the winter on the Chinese side, to wait till the skirmish was over. But it was his fate to remain in foreign land for ever, and my father was to “pass the winter” for forty years in exile . . .

The towns and settlements in Chinese territory, starting with the Manchzhuriya border station, were overcrowded with people. People took up residence in hastily dug-out zemlyankas. At first, there were no earnings at all. And yet, in spite of the magnitude of disaster, the refugees were able to settle down and establish a tolerable life in a foreign land even faster than the Reds, as they were called, at home. The church in the town was a parish school too. It, like many other things, was established by a young bishop sent to Manchzhuriya, Bishop Jonah (secular name Vladimir Pokrovsky), whom father remembered in his prayers all his life. In his three years of serving as a bishop in Manchzhuriya, Jonah managed to establish an orphanage, a lower primary school and an upper primary school with free training in trades, a dining hall that fed, as they said, in Christ’s name, up to two hundred people every day, and a library for religious education. The ambulatory care clinic that was set up in his time provided free of charge medical assistance and medicine to the town’s poorest inhabitants.[6] All this, of course, required considerable funds. And Vladyka knew how to find them.

Even before the revolution, a stratum of Russian industrialists and entrepreneurs had formed in China, especially in its Northeast part, along the CER (Chinese Eastern Railway). It must be said that these were people with a completely different outlook and different human qualities compared with many Russian business people nowadays. They did not take the wealth out of their country; on the contrary, they earned for it. Brought up in religious faith (not all of them were members of the Orthodox Church), in the spirit of patriotism and in the then accepted traditions of philanthropy and patronage, most of them with sincere sympathy perceived the misfortune of their compatriots, who because of the civil war found themselves in the position of refugees. In this respect, the widow Elizaveta Nikolaevna Litvinova, who in the town of Hankou ran a large tea company, stood out in particular. A generous trustee of orphanages and almshouses for the elderly, she would ever-willingly help those in need regardless of ethnic group and religion and subsidise many people with disability, teachers and professors. Litvinova’s special love and care was enjoyed by the House of Mercy in Harbin and Bishop Jonah’s orphanage in Manchzhuriya, of which she was an honorary trustee. She was called “the orphan’s mother.” Elizaveta Nikolaevna was an outstanding person; she herself would read in the kliros, sing in the church choir and even ring from the bell tower. A native of Tyumen, she lived her whole life in China and sincerely loved the country; she knew Chinese and English very well and had many friends among Chinese intelligentsia and entrepreneurs. On top of that, she would invariably wear Russian ethnic dress: on weekdays a black sarafan with a matching black kokoshnik, and on holidays white Russian[7] clothes with a white kokoshnik. She looked striking, youthful, and wherever she was seen—in Shanghai, Qingdao or Tianjin—everyone would stop in interest to take a moment to admire this stately Russian boyarina[8].

In addition, Bishop Jonah knew not only how to ask but also how to demand. Notable for his cheerful, unaffected and sociable personality, he could, when necessary, speak like a power that is, as they say, like a Prince of the Church. At that, he had the gift of quickly getting to the heart of complex economic and financial issues and showed remarkable judgement in business matters. With the help of local patrons (I’ll name them; who else will remember!) the Ganins, Tuliatos, Yalam, Sapelkin and Ashikhmin, Vladyka established small enterprises that gave jobs and income to the poorest inhabitants. Particularly famous was the pottery; its crockery, of rare sturdiness and beauty, was renowned even at the Harbin bazaar[9], just like the most delicious “bread from Yalam.”

Fr Jonah had infinite trust from both business people and the town leaders; they would lend money and entrust large sums of it. If necessary, Vladyka wasn’t ashamed to personally go round to traders. He once even went to furs merchant Mordokhovich to ask for help with the upkeep of the orphanage. “But I’m of a different faith; I’m Jewish,” said Mordokhovich. Vladyka replied, “When I see an orphan on the street, hungry, in rags, I do not ask him of what faith he is; to me, he is simply an unfortunate child who must be fed, clothed and treated kindly.” “What could I say?” told the old Jew. “Before me stood a person of rather short stature, in a little old, patched-up cassock, but from him came an amazing radiance. I became ashamed of my words, and from that day, I began to help his orphanage.”[10] Even the Soviet consul couldn’t remain indifferent to the appeals of Vladyka and would provide the orphanage and the school with coal.

Saint John of Shanghai would say in a lecture on the spiritual state of the Russian émigrés that “The school of refugee life regenerated and elevated many people morally. One must honour and respect those who bear their cross of the refugee, performing work that is unaccustomed, difficult for them, living in conditions of which they never before knew and thought, and notwithstanding that remain strong in spirit, retain nobility of the soul and a passionate love for their homeland and without a grumble while confessing their previous sins, stand the ordeal. Truly, many of them, both men and women, are now in their own dishonour more glorious than in the times of their glory, and the riches of the soul acquired by them are now better than the material riches left in the home country, and their souls, like gold purified by fire, have been purified in the fire of suffering and burn like bright icon lamps.”

My father would recall how he himself, as an eight-year-old, on his own initiative, like Little Philip[11], turned up at Bishop Jonah’s school, straight to class.

“Wherever were you before?” asked the teacher. “It’s late now; enrolments have been finalised.”

Then she took pity:

“All right then, sit here for a bit; I’ll have a talk with the principal at the break. You’re a clever man for coming.”

“That was how I began learning”—I’m reading my father’s childhood impressions in his notes. “At the school, we were given tea to drink every day, and sugar and rusks were put on the tables on large plates; you could take as much as you wanted. The poorest children were given their textbooks and exercise books or clothes too. I won quilted trousers in a raffle at the Christmas tree celebration; they were warm to wear to lessons in winter. Vladyka Jonah would often visit the school and when doing so would, without fail, drop in at each classroom. Many, so many of us learnt to read and write thanks to him.”

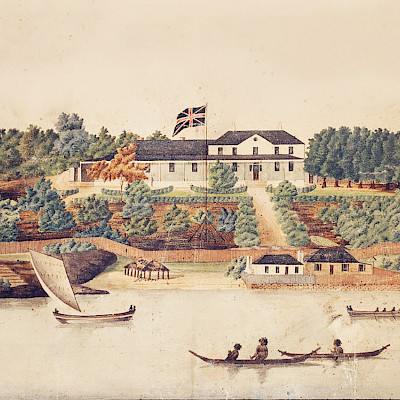

A fragment of the Empire

In the absence of a stable centralised power in China, the Russian émigrés developed in the conditions of a spiritual freedom entirely comparable with and in some ways even exceeding the degree of freedom in the West. The hundreds of thousands of settlers, who continued to consider themselves subjects of the Russian Empire, themselves established usages and laws in the territory of their settling, and they were protected by their own armed detachments and police. Elected atamans governed in Cossack areas. Everyone who saw the Harbin of those days mention the striking unique identity of the city, its stability and loyalty to traditions. When everything turned upside down in Russia itself with the revolution, here remained intact an islet, a Kitezh of Russian patriarchal character with its working and celebratory grandeur, enterprise and conservative steadfastness of its way of life. The authorities changed, tsarist at first, then Chinese, Japanese and Soviet; the city, of course, also underwent changes and adapted itself, but the core of its spirit, its genuine Russian spirit, remained alive, untouched, so it seemed a Russian city on foreign soil was sailing against a current, like a trout in a mountain stream.

“I believe that China, which at just the right time of 1920 took on a large portion of refugees from Russia, gave them such conditions of which they could only dream,” remarked the well-known writer from Russia Abroad Vsevolod Ivanov[12] in his studies on Harbin life. “The Chinese authorities did not interfere in any Russian affairs. Everyone could do whatever they liked. All the engineers, medical and academic doctors, professors and journalists were working. The newspapers Russkii golos, Sovetskaya tribuna, Zarya and Rupor and the magazine Rubezh are published in Harbin. The censorship is merely conditional; the main thing is not to offend the important people. Books are generally published without any censorship.” “There is not a Harbin Russian who does not remember with deep gratitude the years of their life spent in Harbin, where they lived freely and easily,” recalled the writer Natalya Reznikova. “One can say with certainty that there was no other country on Earth in which Russian émigrés could feel so much at home.”

The Russian language was officially recognised, doctors and lawyers could practise freely, and business people opened enterprises and shops. Teaching in gymnasiums[13] was conducted in Russian and in accordance with pre-revolutionary Russian curricula. Harbin remained a Russian university town and at the same time a multiethnic cultural centre, where zemlyachestva[14] and communities of immigrants from the Empire lived harmoniously and interacted closely—Poles and Latvians, Georgians and Jews, Tatars and Armenians. Young people in Harbin had the opportunity to study at three university faculties and the Polytechnic Institute. The best musicians gave concerts at three conservatoires, and Mozzhukhin, Chaliapin, Lemeshev, Pyotr Leshchenko and Vertinsky sang on the opera stage. Apart from Russian opera, in operation were Ukrainian opera and drama, an operetta theatre, a choir and a string orchestra. Student of the local polytechnic institute Oleg Lundstrem established his jazz orchestra here in 1934, which still sets the tone for Russian jazz. About thirty Orthodox churches, two church hospitals, four orphanages, three monasteries and one convent operated in the city. There was no shortage of priests either; they were turned out by the theological college and the university’s theological faculty. In contrast to European countries, where the émigrés of the second generation already were noticeably assimilating and mostly trying to vanish among the indigenes, the Russians in China barely mixed with the local population. Above all, they continued to consider themselves subjects of Russia who only temporarily found themselves beyond its boundary.

Literature expanded in China in the ’20s and ’30s and became a separate flowering branch of the literature of Russia Abroad. Published here were detective stories and historical research papers, political pamphlets and philosophical treatises, home classics and books for children, works in oriental studies and technical literature and, like everywhere in the Russophone world, a multitude of poetry collections. In the space of thirty years (1918–1947), according to data from researchers on this subject Vadim Kreid and Olga Bakich, about 180 collections of verse—sole-authored and edited ones—were published in Harbin and Shanghai. Thus, the literature of Russian China can compete in volume with that of an entire European country. The print runs of those anthologies largely correspond to those of poetic publications in present-day Russia (it is worth noting that the whole Russian population in China did not exceed 500,000). Magazines and newspapers, regarding long-surviving or ephemeral ones, came out in such a great number that it’s hard to even count them. For instance, 60 periodical publications existed just in Harbin alone in 1922. The contemporary Chinese researcher Diao Shaohua[15] calls such abundance and variety “a rare phenomenon in the history of world journalism.” Not in every country where the émigrés found themselves refuge was a thick literary magazine published; in Harbin this magazine, Russkoe obozrenie, was founded back in 1920. In all, magazines numbered about 170, so Harbin Russian poets, unlike the literary youth in the West, had somewhere to have their works published. Writers in Harbin mostly engaged in their professional work and did not work as taxi drivers and waiters, like in Paris.

Of course, the most famous pre-revolutionary writers and poets found themselves in Europe. The eastern branch of Russian literature was left to its own resources. From Paris, Berlin and Prague, people took little notice of Harbin and Shanghai and did not keep up with these cities’ literary lives much. Nevertheless, poets from “Russian China” such as Arseny Nesmelov, Aleksei Achair, Valery Pereleshin and Nikolai Shchegolev were well known to the western émigrés and had their works published in European magazines and anthologies.

Living according to two calendars

The August of 1945 flew by like a thunderbolt and the flood of a torrential summer downpour. Soviet aircraft struck railway bridges and crossings on several approaches. The station was burning. The highway shook at night from the retreating Japanese military vehicles. Soviet tanks appeared, and after them SMERSH detachments too. More than 15,000 Harbin Russians were forcibly taken to the USSR. Among them were the poets Achair and Nesmelov and many Russian émigré figures. The whole of Manchuria had been shaken up several times by the war, and it became clear that previous life would be no more. This unique island of pre-revolutionary Russian civilisation, which for a quarter of a century had stayed in the “old world” was being lashed by the waves of an unknown formidable force, though which expressed itself in the mother tongue. In particular, its structure, which in former times seemed secure and permanent, gave a lurch and began to crack in an instant. They lived there for decades; they settled down and cultivated the land, set up factories, raised and taught children, buried the old, built places of worship and roads . . . and the land proved to be foreign all the same: the time had come to leave it or to obtain Chinese citizenship. Red China didn’t want to put up with the million-strong Russian population that was keeping aloof any more. With Stalin’s death, the attitude in the Soviet Union as well to the émigrés began to change; the past enmity and irreconcilability lost their intensity and were to be long forgotten. In 1954, a formal call resounded from Moscow to the kharbintsy[16] to return to the homeland.

Soviet influence in Manchuria became defining immediately after the war. White Guard organisations were disbanded, and propaganda of the “White idea” banned. Books, newspapers and films began to come in from the USSR. At school, children were already learning from Soviet textbooks; at the same time, Father Alexei continued to enlighten us through scripture lessons too. People lived according to two calendars. So I, looking at the Soviet one, inform grandmother, “It’s a holiday today: Day of the Paris Commune!” She hands me her calendar, a church one, “What commune, for heaven’s sake? Good Lord above! Martyrs today; just you try reciting me their Akathist.” No one at our place knows how to celebrate the Paris Commune, and I, of course, set off to church with grandmother for vespers to pray to the holy martyrs.

On high days and holidays—and at our place right up to our departure only church, Orthodox ones were celebrated—the grown-ups would revel grandly, merrily, and sing old songs and romances preserved from the old Russia; on the quiet they could strike up even Bozhe, tsarya khrani! (God Save the Tsar!). The young people, though, already knew Po dolinam i po vzgor’yam (Partisan’s Song[17]), Katyusha and Shiroka strana moya rodnaya (Wide is My Motherland). Nevertheless, the old-regime structure largely remained intact. On Sundays both one and all went to church, everyone would remember their prayers, many people would adhere to the fasts, and in every home in the icon corner would icons gleam and icon lamps light up. People would mostly dress in the old fashion too, in Cossack or civilian, and what is more, on days of festivities the table would be made up of dishes from the old cuisine; the names of many you’ll now only come across in books. The women religiously preserved and gave the younger ones, their daughters and daughters-in-law, recipes of Russian hospitality. Every festive occasion was surrounded with a special set of viands. People feasted in style, with large, loud celebratory meals, and the revelries would quite often pour out from the houses onto the streets. But there was no dark drunkenness, and on working days, without a reason, drinking was not welcomed and practically did not even occur. Every single one of all the “enthusiasts” was known; they became a laughing stock and to some extent outcasts. People worked thoroughly and earnestly. And they didn’t just “slog away”; rather, they knew how to start up a business, raise capital, learn the necessary professions and establish business relations with foreign countries. That’s why the Russian colony stood out with relative prosperity and order in a sea of at that time destitute Chinese inhabitants.

Of course, not everyone lived equally. The joint-stock company I. Ya. Churin & Co., which had adapted to life in China before the revolution, possessed tea and confectionery factories, a network of stores, including abroad, and tea plantations. Other wealthy factory owners, bankers, merchants, publishers, cattle breeders and concessionaires stood out too. There was a stratum of hired workers and farm labourers, but the main part of the Russian population was made up of small private traders who kept their own farm or had some business in the city. Russians continued to maintain the CER.

It is understandable that the call from the USSR to return was perceived in different ways. Many were not at all pleased by the prospect of coming under the authority of communists and enduring socialism, which, as it subsequently turned out, many émigrés had rather the right idea about after all. Therefore, when at the same time missions from Canada, Australia, Argentina and the RSA began enlisting people for departure, a noticeable portion of Harbin Russians set out for these countries, but my father decided otherwise: America, he said, let the rich go there, and it was more loyal for us to return to our own country. This was all the more because the Soviet consul would at gatherings and receptions paint wonderful pictures of future life in the Union. We children received the news of our departure with delight. In our dreams appeared big, bright cities, a sea of electricity and wonders of technology. Power, energy and an invincible force were felt while making the very sound combination “USSR.”

Quarantine life

After several hours of bumpy road, the vehicle turned around at long flat barracks resembling Chinese fanzas[18]. We were closely surrounded by women and children. They were all eyes and gloomily silent. That’s when, I remember, I, an eight-year-old, suddenly became afraid, and in my heart I felt how far we had gone from our home region and from our usual life and that you will now not return there and will have to live among these people who you cannot understand. After taking a stool given from the body of the vehicle, I carried it towards the doors; the crowd before me parted in fright. Later on, the “locals” confessed that they had been expecting real Chinese people to come to their village, whom they probably imagined wearing silk robes, with small queues[19] and holding fans and umbrellas. Our simple appearance surprised and disappointed them.

Lying ahead of us in this gloomy damp dump with walls that showed through from their thinness (later we pasted them over ourselves with clay to make them a little thicker for winter) was spending two years in quarantine conditions: we had to get accustomed to Soviet usages little by little. Moldovans exiled to Siberia after the war huddled in neighbouring barracks. There were some Roma families too that found themselves there for the campaign of taming for settled life announced at the time by Khrushchev. Their non-depressing disposition, singing and dances to the guitar and the fights and quarrels between the kiddies imparted the picturesque colour of a Roma camp to barrack life.

Little by little, locals did begin to appear at our campfires. In the beginning, they didn’t bring themselves to become close friends with us; after all, we were people from abroad, under supervision. It was the children who were the first ones, as always happens, to grow bold and become acquainted among themselves, and their mothers after them. At first, the women watched from the outside in silence, refusing to cross the threshold or sit down at the table. The guys became friends more quickly, but men in the village were few, especially healthy ones who were not maimed. It was learnt bit by bit from conversations what happened here before our arrival and how, what great misfortune the country overcame only a few years before and how much grief came with it into nearly every village home. Even our own hardship seemed minor and not vexing before these people’s ordeals and losses. And just how much only lay ahead still for us to learn and understand, to accept into our hearts so as not to for ever remain strangers, newcomers, so as to properly, intimately unite ourselves with those living alongside us, with this land unfamiliar for the time being, albeit also our, Russian, land, and our own fate with a common destiny. After all, only then could a true return and finding of Russia take place, not of the Russia imagined through song, bylina and by émigré, but of the Russia of the present, of where we were, of Soviet Russia. But this did not come naturally . . .

Every morning between about five and six, the sovkhoz cleaner would hammer on the windows of the barrack and call out to the occupants, informing them of who was to go to what work. Any day it would be different. I can still hear this rattling on the glass and nasty shouting that scares a child’s sleep away.

My father could do, it seems, any work. If I were to take it upon myself to count, he had command of a few dozen of the most useful trades: he was able to put up a house on his own, a wooden one, a stone one; set down a stove; acquire ploughland or produce cows and sheep in great numbers; dress leathers and sew some caps, boots and sheepskin coats with his own hands; he knew the habits of wild animals and knew how to treat domestic ones medically; he knew how to find his way in the steppes and in the forest without a map and without a compass; he had a command of Chinese and Mongolian at an everyday level; he played the garmon and in his youth even acted in amateur dramatics; and for a few years he was an ataman, i.e. engaged in zemstvo work. But all that which had been acquired and accumulated in that life immediately proved to be unneeded and useless in this one, where they “drove” you to work (people would simply say “Where are they driving you tomorrow? Yesterday they drove me into the sowing area”). Here, it was impossible through any ability, effort or persistence to improve anything, do anything your own way or make life easier for your family. It was as if the settlers were left without the hands with which even yesterday they had been able to do so much. There were things to despair and fall ill from. The cemetery in the small neighbouring grove grew greatly in the space of two years with the graves of “Chinese people.” But when the period of quarantine approached its end, those who survived began to disperse. It was the young people who were the first ones to rush at exploration. The sovkhoz management delayed documents, didn’t grant leave and intimidated the people there, but they flew away, like sparrows. The Roma had wandered away somewhere for a better fate even before our departure.

Time makes equal

A few years ago, I again visited the sorrowful settlement to revive the memory of my childhood years and visit the graves. On the site of our barracks, I saw a long row of small mounds and holes that had become overgrown with tall weeds, and everything else, the dwelling areas, had become even more dilapidated and lopsided. It seems not a single new building has appeared there in fifty years.

For the first years, the repatriates still held on to each other, observed their customs, chose to marry their own people, associated with each other and paid each other occasional visits. Even today in some cities in Siberia and Kazakhstan there are zemlyachestvo[20] of former Harbin Russians, and in Yekaterinburg, albeit irregularly, there is even an amateur newspaper that comes out, Russkie v Kitae. But already their children began to forget their old community and relations, grew washed out and became fully Soviet. From father, I am able to judge how the views and moods of former émigrés changed with time. “Living there was more free and more interesting, and here it’s easier, calmer,” he said in his old age. In the seventies, he was somehow found and visited by a cousin from Australia, also a former Harbin Russian. Twenty years later, it was already hard for them to understand each other. They had been taken off from the ice floe called Russian Manchuria and conveyed to different continents. But the ice floe itself had melted . . .

In the thirties already, the Harbin Russian poet Arseny Nesmelov, who perished near Vladivostok in a Grodekovo transit prison in December 1945, foretold the future of his city:

Dear town, proud and harmonious,

There will be such a day

When people will not remember that you were built

By a Russian hand.

Though such destiny is bitter,

We will not cast our eyes down:

Remember, old historian,

Remember us.

You will find what has been forgotten,

Enter it on the case history,

And into the Russian cemetery

Will a tourist run.

He will take with him a dictionary

To read the inscriptions. . .

Thus will our small lamp go out,

By getting tired of flickering![21]

Gennady Litvintsev

Translated by Samuel Brotchie

[1] English translation: “repulse”; “rebuff”

[2] English translation: “friendship”

[3] I believe that Great Russian here is not to be understood in the historical sense; rather, I believe that it is a combination of two separate adjectives.

[4] The English meaning of бурка suitable for this context is “felt cloak (worn in Caucasus)” (Oxford Dictionaries, n.d., para. 1).

[5] I have decided to transliterate into English the evident Russian transliteration of this Mongolian word as it appears in the original article. Additionally, I believe that the Russian transliteration of this word as it appears in the original article has been misspelt, so this is reflected in my English transliteration of this Russian transliteration.

[6] My translation of a section of text from the corresponding Russian paragraph in the original article (from In his three years to to the town’s poorest inhabitants) was verified against a pre-existing translation of text with identical and similar elements; this pre-existing translation and text are in Gradov (2014, pp. 28–29), and my translation (from In his three years to to the town’s poorest inhabitants) contains some elements that were taken from and some elements that are similar to elements in Gradov (2014, p. 29).

[7] I believe that white Russian here is not to be understood in the historical and political sense; rather, I believe that it is a combination of two separate adjectives.

[8] Masculine form: “boyar”

[9] My translation of a section of text from the corresponding Russian paragraph in the original article (from With the help of local patrons to the Harbin bazaar) was verified against a pre-existing translation of text with identical and similar elements; this pre-existing translation and text are in Gradov (2014, pp. 27–28), and my translation (from With the help of local patrons to the Harbin bazaar) contains some elements that were taken from and some elements that are similar to elements in Gradov (2014, p. 27).

[10] My translation of a section of text from the corresponding Russian paragraph in the original article (from If necessary to I began to help his orphanage) was verified against a pre-existing translation of text with identical and similar elements; this pre-existing translation and text are in Gradov (2014, pp. 25–27), and my translation (from If necessary to I began to help his orphanage) contains some elements that were taken from and some elements that are similar to elements in Gradov (2014, pp. 25, 27).

[11] Little Philip is one of the English-language titles of the (transliterated) story title (and by extension one of the English-language names of the [transliterated] character name) Filipok (or Filippok) by Leo Tolstoy.

[12] I believe that the forename and surname of this writer refer to Vsevolod Nikanorovich Ivanov and not Vsevolod Vyacheslavovich Ivanov.

[13] Gymnasiums here refer to the educational institutions.

[14] Singular form: zemlyachestvo

[15] I have used a transliteration of this researcher’s name based on popular usage.

[16] An English translation of this word in this context might be “Harbin Russians.”

[17] This is not a literal translation of the Russian title; I decided to use a popular, established English variant of the title to facilitate the reader’s searching for the song should they wish to.

[18] The English meaning of фанза is “fanza (a peasant house in China or Korea)” (Oxford Dictionaries, n.d., Fanza [Fanza] section).

[19] A queue here refers to the style of hair.

[20] Singular form: zemlyachestvo

[21drew from comments made in Meng Li (2004, p. 490) for translating lines of this poetry.

Translator’s note

This translation is a translation of the original text and was completed by me in 2020 during my bachelor honours degree programme in the field of Russian.

I am not a professional translator and have no formal translation qualifications. Any mistakes in this translation should be considered in this context. Any views expressed in this translation are not a reflection of my views.

If any text in this translation contains text from external sources, this is indicated in this translation, and the details of these sources can be found in a list at the end of this translation.

I feel privileged to have had the opportunity to produce this translation, and I hope that it is of benefit to the literature on Harbin Russians and to the Unification community.

Samuel Brotchie

February 2021

__________________________________________________________________________________

List of external sources used in this translation

Gradov, Z. (2014). Svyatitel' Iona Khan'kouskii: Apostol lyubvi/St. Jonah of Manchuria: Apostle of love (M. Wroblewski, Trans.). Vesna dukhovnaya/Spiritual Spring, 2(1), 22–29. https://issuu.com/ellephemister/docs/spiritualspring_issue_3

Li, M. (2004). Russian émigré literature in China: A missing link (Publication No. 305098916) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Chicago]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Oxford Dictionaries. (n.d.). Burka [Burka]. In Oxford Dictionaries Russian. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://premium-oxforddictionaries-com.ezproxy.library.uq.edu.au/translate/russian-english/бурка

Oxford Dictionaries. (n.d.). Fanza [Fanza]. In Oxford Dictionaries Russian. Retrieved October 26, 2020, from https://premium-oxforddictionaries-com.ezproxy.library.uq.edu.au/translate/russian-english/фанза