A significant international conference devoted to the centenary of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (commonly called the “Church Abroad” by its parishioners) took place in the Serbian capital, Belgrade, on 23-25 November 2021. The conference carried the blessing of Metropolitan Hilarion, First Hierarch of the ROCOR. The conference was attended by Metropolitan Mark of Berlin and Germany, who did not miss a single presentation and gave a succinct summary of the topics covered at the end of each day.

Our ROCOR was established in the small Serbian town Sremski Karlovci, which gave the Moscow Patriarchate cause to call us, the children of our church “Karlovites” with condescending deprecation.

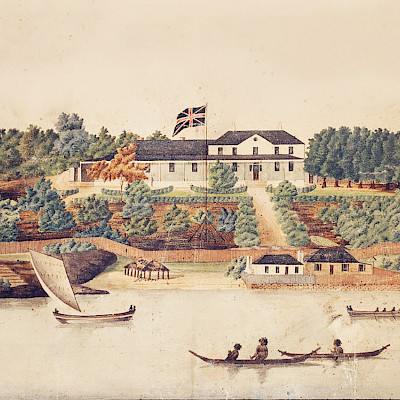

The holding of the conference in Belgrade and Sremski Karlovci had both historic and symbolic significance, as after the tragic events of 1917 in Russia, it was the Serbian Orthodox Church that permitted the foundation of this new religious body on its territory, and also protected and supported the Russian diaspora in the 1918-1939 interwar period. It may interest our readers that up to the end of the 1940s, the Serbian Orthodox Church had no presence in Australia. Its parishes appeared in Australia and New Zealand only after the Serbian diaspora grew considerably after those who rejected communist ideology – including numerous clerics and their families – were driven out of Yugoslavia.

In view of the aforesaid, it is not surprising that this academic forum was convened on the initiative of the Archive of the Serbian Orthodox Church in the person of Dr Radovan Pilipovic and the Internet resource “Questions of the History of the Russian Orthodox Church” in the person of church historian deacon Andrei Psarev (Jordanville).

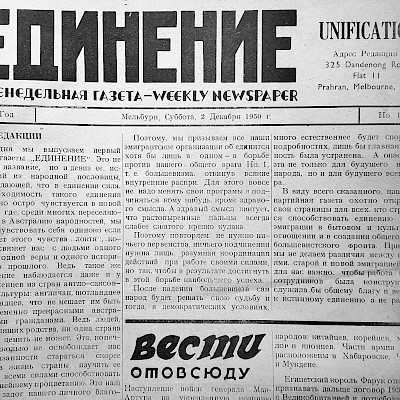

I was privileged to be invited to the conference due to my many years of narrating and co-authoring the Russian religious programs of Radio Liberty and the Russian Service of the BBC. I apologise in advance to readers of this report for my possibly unduly subjective perception of some aspects of my visit to Belgrade, but firstly I would like to refer to the conference as such. I note with great pleasure that the program of the conference was packed with exceptionally comprehensive and interesting presentations, something that cannot always be said of academic forums. In this instance, all the lecturers were outstanding specialists in their various fields. There is no space in this report to list them all, suffice it to say that readers interested in the subject should be able to access the materials of the conference on the Internet site Questions of the History of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (www.rocorstudies.org). The scholars making presentations at the conference came from as far afield as Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Serbia, USA, Canada and even (online) from Australia. Unfortunately, the presentation from Australia by priest Nemanje Mrdzenovic from the St Nicholas Serbian Orthodox Church in Blacktown (NSW) on the subject “Relations between the ROCOR and the Serbian Orthodox Church in Australia 1950-1969” had to be abandoned after numerous attempts due to serious technical disruptions.

Having been born into a White Russian family in the then existing Yugoslavia, I believed myself to be quite well-versed in Russian history, the story of the Russian exiled diaspora and the history of the ROCOR. Alas, it turned out that there was something unknown to me in just about every presentation. I was particularly interested to hear the presentation by Svetlana Nikolayevna Bakonina, a senior researcher at the St Tikhon Holy Trinity Humanitarian University in Moscow, on the subject “The Far Eastern church district as an alternative to the Higher Church Administration Abroad related to the question of its closure in 1922.” Maybe some of the readers of this report are better informed, but I admit that I knew nothing whatsoever about this issue.

The conference was divided into 8 parts: 1) The Russian Orthodox Church in exile prior to the formation of the ROCOR; 2) World War II as a continuation of the Civil War in Russia; 3) The formulation of canon law in new conditions; 4) Relations between the ROCOR and the Serbian Orthodox Church; 5) Russian Orthodox immigrants in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians in Yugoslavia; 6) Events in the course of World War II; 7) The ROCOR and the North American Metropolis; 8) Conclusions and Perspectives. In other words, the scope of the conference was a very broad one.

On the morning of 23 November, the participants of the conference went to the Russian church of the Holy Trinity to attend a requiem service for Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky) who became the first head of the newly formed ROCOR. For me, attending this church had special significance as it holds the tomb of General P.N. Wrangel, the last leader of the White Movement. His memory was always cherished in our very White Guard family as my maternal grandfather, colonel Vladimir Pavlovich Komarov, remained with Wrangel to the very end, the evacuation of the remnants of the White Army from Crimea. From childhood, I knew the story of the reinterment of General Wrangel’s remains from Brussels to Belgrade. The marble slab covering the tomb is located beside the Cross of the Crucifixion and a column bearing the imperial gold double-headed eagle. The regimental standards that had been brought out of Russia by the White Army were looted when Soviet forces entered Yugoslavia during World War II. According to my relatives, the clergy of the church of the Holy Trinity barricaded Wrangel’s tomb with a huge icon of the Day of Judgement, and it remained untouched.

A second memorable event for me was an excursion on the second day of the conference to Sremski Karlovci where the seminary of the Serbian Orthodox Church is located and the place where the aforementioned Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky) and General Wrangel had lived for some time. The huge, amazing historical church complex at Sremski Karlovci is rich in marvellous exhibitions, to say nothing of breathtakingly beautiful churches. Yet it was in this memorable place that I suffered a painful disappointment. Somebody mentioned that the house in which General Wrangel had an apartment was just outside the church territory. I joined a group that walked to see this two-storey house, which for us was a historical landmark. I wish I had not gone. To say that the house is practically derelict is to say nothing. Its facade is dark with dirt, half the windows are smashed and replaced by plywood sheets, the wooden shutters are broken and hang crookedly on a nail or two. On the wall to the right of the front door there is a grimy plaque stating that General P.N. Wrangel had lived in this house in 1922-1926. Some people and children - presumably current tenants of the place – were sitting on the footpath outside the entrance. Sadly for us, the rooms once occupied by the Wrangels were no longer open to visitors. It was painful, bitter to look upon this evidence of degradation. As far as I know, there are monarchist societies in the Russian communities of various countries: surely they could unite their efforts to rescue this historically significant building that had once housed what was left of the White Russian high command?

Incidentally, at the end of this day trip we were shown an excellent documentary film “His Excellency Baron Wrangel” with Russian subtitles by the Serbian cinematographer and director Bosko Milosavljevic. Here I had an unexpected, pleasant surprise: on a 1921 photograph in the documentary showing General Wrangel visiting Russian scouts on the island of Prinkipo near Constantinople, I saw my then 11-year-old aunt, my mother’s older sister Irina. Aunt had told me about this meeting with Wrangel. Russian scouts are traditionally given a “forest name” after passing their Second Level tests. Seeing how agile my aunt was in climbing a tree, Wrangel laughed and said: “You must surely be “Little Monkey” (“Martyshka” in Russian). Needless to say, aunt was not at all offended.

The changes of positive and negative impressions continued the next day. Preparing to travel to Serbia, I set myself the aim of visiting the grave of my great-grandmother, Elena Alexandrovna Dudyshkina, nee Engelgardt, (1860-1933). I knew from friends who had occasion to visit the “White Russian” section of Belgrade’s “Novi Groblje” cemetery, that her grave was in excellent condition, as that part of the cemetery was maintained in order by Serbs who considered it to be part of their national heritage. However, nobody from our family had been at that grave since 1944, when we, along with other White immigrants, were forced to flee for our lives from Yugoslavia in the face of advancing Soviet forces.

I was warned by one of the participants of the conference that the old Russian cemetery was undergoing a “reconstruction” financed by Gazprom on the initiative of the “Istochnik” (“Source”) fund, organized with the support of the Belgrade representation of the Russian Orthodox Church, the embassy of the Russian Federation in Serbia and the Belgrade mayor’s office. I do not deny for a minute that it is quite proper to deal with derelict or abandoned graves, but I was horrified by the prospect of still perfectly sound monuments, that may have historical significance, being transformed into grey, soulless rows of identical stone slabs with the same-sized crosses like the war cemeteries one sees in the north of France and other countries where great battles had been fought in past wars. Judging by current Google Earth aerial photographs of the Novi Groblje cemetery, about a third of the “old” graves have not yet been subjected to “reconstruction”, but they are doomed to standardization. Thank God, great-grandmother’s grave has not changed radically and was easily found on the map issued by the cemetery administration It is right behind the chapel, and near the imposing monument erected in memory of the fallen in 1914 and later, bearing the legend “Sleep, fighting eagles” (“Spite orly boyevye”) above its entrance. I only hope that the Gazprom philanthropists do not decide that it, too, could do with some “reconstruction”…

Thanks to the assistance of Alexander Mustafin, a young photographer some of whose photos accompany this report, it proved possible for a short memorial service (“litiya”) to be served at great-grandmother’s grave for the first time in 88 years.

Eternal memory and deserved rest to you all, who lost your homeland in accursed, tumultuous times. May the Serbian earth lie upon you as lightly as a feather!

Elena Glebovna Kojevnikova, nee Berdnikova. England.