Recently I shared with an acquaintance of mine what I was planning to write, and he asked me in response: «And who is interested and needs it nowadays and why waste time on it?» I don’t think he’s right. This article is a tribute to the memory of a remarkable Russian woman Nina Nikolaevna Fomina-Shudnat who was from the large Bibikov family in Ekaterinburg, headed by the then prominent lawyer and public figure in the Urals, Savel (Sever) Alexandrovich Bibikov. She was his granddaughter. The fate separated her at an early age from them and her parents Strelnikovs and her two sisters, and in the early 1950s she found herself in distant Australia, in Hobart, where she lived a long and meaningful, interesting life and left a kind memory of herself. And in Russia, quite recently a documentary film was made about Strelnikov sisters. She was one of the film’s heroines.

I’ll say something briefly about the film further down and would like to start with the story of Nina Nikolaevna Fomina-Shudnat, its Australian heroine, based on the recollections about her by people who knew her and from other sources — about her 88-year life journey which saw its beginning in Ekaterinburg in the Urals and in Vladivostok, continued abroad in Harbin and Shanghai in China and came to an end in a far away from her homeland Hobart

The Bibikov family in Ekaterinburg had nine children: three boys and six girls (Boris, Vladimir, Sever, Nina, Zoya, Lydia, Nina, Alexandra and Tamara). Alexandra Savelovna (1892–1980) was her mother. Nina’s grandfather Savel Alexandrovich died in Ekaterinburg in 1918, her grandmother Lydia Vasilievna (née Betaki) died there in the early 1930s. Vladimir and Boris were shot in Krasnoyarsk in 1920. Nina’s mother, Alexandra Savelovna, was married to Nikolai Dmitrievich Strelnikov (1872-after 1919), and they had three girls Alexandra (1912–1989), Tatiana (1913–1977) and our heroine, Nina. She was born in Ekaterinburg on January 25, 1914.

With the beginning of the mass exodus of Russians from China in the early 1950s, among those who migrated to Australia from Shanghai was the film’s heroine, 37-year-old Nina Savelovna Fomina-Shudnat, nee Strelnikova, granddaughter of Savel Alexandrovich Bibikov, formerly well-known lawyer and public figure in the Urals, and his wife Lydia Vasilievna, nee Betaki. She arrived with her widowed 71-year-old aunt Lydia Savelovna Shudnat in the first month of Australian spring in September 1951. In immigration documents, Nina’s year of birth was wrongly recorded as 1919, not 1914. Judging by her photographs, she was a beautiful stately woman.

Nina’s husband Oleg Fomin, the son of a well-known public figure in Shanghai and naval officer Captain 1st Rank Nikolai Yuryevich Fomin, died in Shanghai in 1947. They had no children. Nina kept her aunt’s surname Shudnat in recognition of the care that she gave her as a mother over the years and provided the opportunity to get a good education in Harbin.

The fact of the matter is that at the beginning of 1920 Lydia Savelovna was asked by Nina’s parents (Alexandra Savelovna and Nikolai Dmitrievich Strelnikov), together with her husband Nikolai Georgievich Shudnat, to travel with their sick niece for treatment from Vladivostok to Harbin. Little Nina was seriously ill with measles and her overall health was at great risk. They thought the trip would only be a temporary one, but it turned out differently — they left their relatives and Russia forever as they could not return because of the military events unfolding in Vladivostok ending with the defeat of the White forces. Nina will never see her parents and sisters Sasha and Tanya again. Lydia’s husband Nikolai Shudnat will die in Harbin during the Soviet-Chinese armed conflict in 1929 and her widowed aunt will continue to raise Nina.

The fact is that at the beginning of 1920, when Lydia Savelovna and her husband Nikolai Georgievich were going from Vladivostok to Harbin, the mother of little Nina Alexandra Savelovna (her husband Nikolai Dmitrievich died on the way from Ekaterinburg) asked them to take with them their niece who needed to get additional medical treatment and recover from the complications she had after contracting measles. They thought that the trip would be temporary, but it turned out differently — they left their relatives and Russia forever, unable to return because of the military events unfolding in Vladivostok, which ended in the defeat of the Whites. Nina will never see her mother or her sisters Sasha and Tanya again. Lydia’s husband Nikolai Shudnat died in Harbin around the time of the Soviet-Chinese armed conflict of 1929, and her widowed aunt Lydia, will continue Nina’s upbringing (making a living working as a nurse and a masseuse).

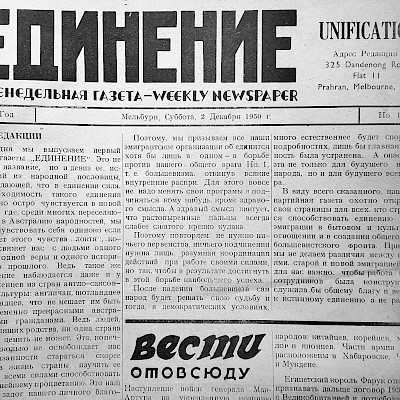

The two of them arrived together in Sydney on the newly built Chinese ship «Changsha» under the program of the International Refugee Organization (IRO), as «White Russian» stateless refugees from China. They didn’t stay in Sydney long and moved to Hobart, where a long-time good friend from China, Georgy Nikolaevich Goloobeff, the son of a well-known surgeon in Harbin Nikolai Pavlovich Goloobeff lived with his family. Georgy Nikolaevich helped them find a place to stay and became one of their close friends in Hobart. See Unification paper’s website article about him. The link is: https://www.unification.com.au/articles/1553989371/

It was not easy for them to start a new life in a new country, as was the case for all emigrants back then. Nina initially worked for many years as a typist, clerk, and took on other jobs. It was a matter of survival. At the time the government did not pay any benefits to immigrants. She set herself the goal of finding a job to her liking and entered college when she was already well over 50 to get a diploma in Visual Arts. She succeeded in achieving this. For 15 years she worked as a teacher at the co-ed Catholic School of the Dominic College, teaching in the senior classes. She taught students to draw and paint. Her former students and colleagues called her by the affectionate nickname «Shudi» and later shared their recollections of her with special warmth and love in the school magazine «Veritas» (see # 10, June 2020, pp. 44–47).

Soon after arriving in Hobart, despite other worries and her substantial workload, she energetically began, with the help of new Australian acquaintances and in particular elderly Tasmanian Mr L.v. Orchard, to bring her other aunt Zoya (Zoe) Savelovna Chairman, nee Bibikova (born in 1883) to Australia. Zoya was an artist living in Harbin at the time with husband, officer Herbert Chairman. Sadly, Herbert died in Harbin in 1934 at the time of the occupation of Manchuria by the Japanese. Nina also began to make submissions to authorities to allow her friends who were stuck in Shanghai to migrate to Australia and on behalf of those who were in a dire situation in Harbin. She looked to find sponsors for them and work as was required for immigration purpose by the authorities. She devoted herself entirely to this task, achieving significant results.

She specifically called on the Australian government to allow a large group of Russian nurses from China to move here. At that time, there was a great shortage of nurses in the country. Nina’s impressive efforts are evidenced by documents in two huge folders filed under her name Shudnat N in the National Archives of Australia, about 400 pages. There you can find the names of the people she made representations for and correspondence with senior immigration officials and ministers — a rich source of research material. One of these officials Harold Holt would later become the Prime Minster of Australia.

In the end, in January 1953 Nina managed to bring to Australia her other elderly aunt Zoya Savelovna Chairman for her to live with them in Hobart. They lived in the suburb Glebe not far from the city centre and the Botanical Gardens. Their nice wooden house stands there to this day on Service Street. About five years after their arrival in the new country, all three of them were granted Australian citizenship and as was customary at the time, were called «New Australians».

At that time, in Hobart, Russians were just beginning to form their community and organize themselves, as was the case in other cities in Australia, around parishes. And Nina became an active member of the newly created Russian Orthodox parish in Hobart of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross. She told the readers of the «Avstraliada» magazine (see No. 11 of 1997, pp. 31–34) how our compatriots settled there and how the church was built. She sang in the church choir. She maintained friendly relations with the family of Georgy Nikolaevich Goloobeff. It was he who helped her acquire the house in which she lived with her aunts and which she furnished with beautiful old furniture, bought a piano, decorated the walls with paintings, and sheltered a homeless cat.

And, of course, music and theatre, the love for which was instilled in her from childhood by her parents and close relatives. She participated in Russian cultural events dedicated to various holidays, organized musical performances with her Australian friends. She also featured on Australian radio music programs. For example, on May 19, 1958, on radio 2BL, immediately after the program of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra (conducted by our renowned compatriot maestro Nikolai Malko), listeners of fine music were presented with another gift — a performance by the vocal duet of Nina Shudnat and Tamara Atkins-Zazoba. In addition, she gave private singing and painting lessons at her home. One of her students, now a famous local singer Zulya Kamalova, recalled her in the press with gratitude.

Nina’s contact with her relatives in Russia was lost when she migrated to Australia. Attempts to find them with the help of the Red Cross did not yield any results, she was sure that none of them survived. It was only in late 1990s, that she learned that her sister Shura died tragically in a road accident in 1989 at the age of 77, her mother Alexandra Savelovna died in 1980, she also died on the road, being hit by a car, and Tanya died in 1977. All of them are buried together in one grave at the Dolgoprudnenskoye cemetery in Moscow

She continued to correspond with her friends in Shanghai, for example, the famous poetess and former dancer Larissa Andersen in France, in Sydney with the former ballerina Nina Kojevnikova (married to Panchenko) and the recently deceased renowned poetess Nora Kruk and with her relative in Sydney, Maria Nikolaevna Fomina-Rosentool (sister of Nina’s late husband Oleg Nikolaevich Fomin), and with many others. Some of these letters survived to this day.

And the years flew by. In 1970, her aunt Lydia Savelovna Shudnat, died, and 12 years later, in 1982, Nina buried her second aunt Zoya Savelovna Chairman. From this moment, she was left to live with her cat and memories. She shared some of her recollections of her past life with a handful of her friends but sadly none of them wrote them down.

Gradually, her health after she was hit by a car began to fail and she fell seriously ill with cancer. Before her death on December 29, 2002, she bequeathed some of her family albums and old letters to her Australian close friend, former colleague and student Jeremy Keane. She believed he would keep them safe, and they would help him learn more about her life, origins, about her sisters and parents, about the fate of Russian émigrés who fled Russia after the Civil War.

Why him? Probably because of their bond brought about by their common interests. He often visited her, and they could talk for hours on different topics. He showed her his work, as a photographer, and took heed of her comments. He asked her a great deal about many things, admired and appreciated her as a person. And when she passed away at the age of 88, he once discovered in the album one of her photographs, on the back of which she had written in a beautiful handwriting a dedication to him in English: «To, а dear young friend who has been dropped from heaven into my house! Here I am facing it at, but at the age of 82." And this inspired him to learn more about her, not to let it all disappear without a trace.

He spent years researching her ancestry, tried to find out something about every photograph in her albums — who were the people depicted in them, what the hand- written annotations were, where and when they were taken. And he tried to find Nina’s relations in Russia. Not knowing the Russian language, he turned to his Russian acquaintances for help. He wanted to write a book about her in English would start and then stop. He then found Valery Vladimirovich Bibikov in Moscow, who turned out to be a namesake to the Bibikovs family from Ekaterinurg and President of a non-governmental organisation «The Russian Union of Revival of Ancestral Traditions». This acquaintance with Valery gave Jeremy a lot of new information particularly when he introduced him to Bibikov descendant a Ryazan the grandnephew of Alexandra Savelovna (Nina’s mother), Vladimir Igorievich Tikhomirov, who at that time was also involved in researching his ancestors in Ekaterinburg.

And as Vladimir recalls, they began to exchange photographs and it turned out that they were from albums related to the same family. They started a difficult task of attributing the many photographs they had. And Vladimir obtained from Ekaterinburg historians a great deal of new facts and documents about the life of the Bibikov family in the Urals. Jeremy on his side continued his research about the life and time of the Bibikovs relations outside of Russia. This took several years. In the end they decided to make a documentary film. There was a story waiting to be told.

And finally, quite recently, the shooting of the planned film which was a collective effort was completed. It consists of four parts with a total duration of 55 minutes and entitled «Strelnikov Sisters from Ekaterinburg». This is a film about the Strelnikovs and Bibikovs from Ekaterinburg, about the death of the Tsar’s family there, about the flight from the Bolsheviks, about the upheavals at the time and about the fate of the three Strelnikov sisters — Tatiana, Alexandra and Nina. And about how Nina, along with her aunt Lydia Shudnat, ended up on the other side in emigration, while other family members remained in Russia. How her sisters Shura and Tanya fared in Russia and how the Strelnikovs made their name famous, achieved recognition by helping opera and pop singers to restore their voice with the help of special breathing exercises invented by them and patented.

And in the words of the author of the film Vladimir Tikhomirov: «The private life of the Bibikov family is intertwined with world events and its history is closely connected with the history of Russia — Bibikovs lived practically next door to the Ipatiev house in which the Romanov Family was shot in 1918…» Nina, recounted to Jeremy that when she was still very little, she came to Ipatiev house with her parents to lay flowers.

Nina’s Australian friend Jeremy Keane co-authored the film. Valery Bibikov from Moscow, Elena Kravtsova from Stavropol and Nina’s friend Natalia Novikova, now a famous film actress living in Melbourne, also took part in the project. Narration (with pleasant voices) was by Vladimir and Galina Tikhomirovs (she is also the film editor) and People’s Artist of Russia Sergei Leontiev. The visuals are accompanied by wonderful music by Schnittke, Shostakovich, Schubert and other composers. . There is also footage in the film of the famous Sergei Jarov’s Don Cossack Choir singing an old Russian folk song. The film has not yet been released in Russia. As for our readers, they can watch and download it «in the Cloud» until October 9 of this year. Here is the link: https://cloud.mail.ru/stock/j9R3ETh7VmgHcE6Tw5nZfJu3. In the future, in Sydney and other cities, after the restrictions are lifted due to the pandemic, it will possibly be shown in our community centres.

The writer of this article first made a work-related visit to Hobart in the early 1980s. It was then that he learned about the existence of the Russian Church there and of the Russians living in Hobart he only met Sergei M. Oldenborger and his family. From memory he was a graduate of the Crimean Cadet Corps. And he learned about Nina Shudnat much later, after her death, when he again had an opportunity to come to Hobart and on that occasion met for the first time Georgy Nikolaevich Goloobeff and Jeremy Keane, who knew her. Jeremy showed him the albums which Nina bequeathed to him, and told how important it was for him to keep her memory alive

And while in Hobart he felt compelled to visit the cemetery where Nina and her aunts were buried. She was buried in the same grave with her aunt Lydia Shudnat. A little further away is the grave of her aunt Zoe Chairman. Similar monuments with large crosses adorn both graves. On one of the crosses in its upper part is inscription «Christ has Risen», on the other — «Truly Risen». At the foot of both crosses is the icon of the Resurrection of the Lord. Inscribed at the base of the crosses in English are their names. However, nothing apart from this is written to help us better know who these people were. Not far away is the grave of Georgy Nikolaevich Goloobeff, who died in 2019 at the age of 103 and was buried with his Australian wife next to the grave of his mother. Nina’s funeral service as he found out was conducted in a local Greek Orthodox Church by its rector Fr Timothy Evangelinidis who also officiated the burial at the cemetery — as he was asked to do by others.

And by way of information to those interested in the history of Russians in Australia the cemetery in question is called Cornelian Bay Cemetery and is thought to be one of the oldest in Tasmania (opened in 1872) with over 100,000 burials. It is located not far from the city on high ground with beautiful views of the bay and mountains. On one of its sections, one can see many graves with traditional Orthodox crosses, which can also be found in other cemeteries across Hobart — evidence of the Russian presence in the picturesque Hobart, a place far away from their homeland.

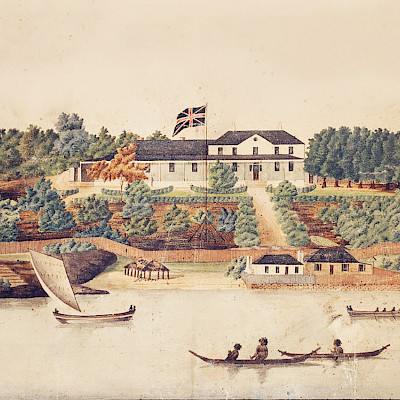

Another notable historical fact of Russian presence in Tasmania is the headstone which is located on the property of the Russian Orthodox Church of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross since 1972. It came from the grave of Grigory Belavin, a purser from the Russian corvette Boyarin, who died on 6 June 1870 when the corvette visited Hobart in May 1870. The corvette left Hobart on June 12 after Belavin’s funeral. He was buried in the city’s first colonial cemetery, St David’s, opened in 1804 when Hobart was founded. The cemetery was closed for burials in 1872, and in 1926 it was converted into a park of the same name — St David’s. There were about 900 burials in the cemetery. Most of the remains were reburied in the Cornelian Bay Cemetery and the headstones were preserved and installed on the walls of a curvy walkway though the park. It is likely that Belavin’s remains were not reburied and together with some others remained somewhere in the park’s grounds. In 1972, the gravestones of former military burials were moved from the cemetery to other locations, and it was then that the city authorities decided to relocate Belavin’s headstone to the grounds of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Nina Nikolaevna Shudnat did not write her autobiography, she left behind only her family albums and letters. Fortunately, there are still people and close friends who have not forgotten her.

Father George Morozoff, priest of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (Hobart, recorded 19.7.2021)

«I visited her at home when she was ill. She used to come to church until she could no longer. Afterwards I used to go to her place after the Liturgy and give her Communion. I went to see her often. I think her funeral was conducted by the Greek priest Fr. Timothy. This was after the split in the church. I regret not being the one who conducted her funeral. At the time I held services at my place. I didn’t even know that she had passed away. Her relative, Father Alexis Rosentool, came to see her before her death, when she was already sick. Later I found out that her death was reported to Fr. Michael Protopopov in Melbourne who asked for the service to be conducted by the Greek priest. When I met her, she was already aged and beginning to lose her memory. But you could immediately see that she was obviously quite intelligent, well-read, and that she was a musician. It was also obvious straight away from the way she presented herself and the way she talked that she was a very educated person. We moved to Hobart in 1995. During all this time, I think I conducted funerals for about 40 of our people. It’s a pity how it happened that the church service was not conducted in our church, where she was a parishioner for many years».

Father Miсhael Protopopov, Dean of the Southern District of the Australian Diocese of the ROCOR, including Tasmania (Melbourne, recorded 19.7.2021)

«I knew her well. At first as a church going person, she went to almost all services. Despite her advanced age in years when I knew her, she always went to church. Sadly, her memory was already failing her and there were oddities and deviations in her state of mind, however she was a very interesting person to talk to. She could talk on any topic, and her stories were endless. I think she even at one time went to the University of Hobart and she taught at a school. At the end of her life, when she could no longer go anywhere, I know that parishioners visited her and the clergy also. I could not visit her often, because I lived in Melbourne, but her house was like a sort of museum. She had lots of interesting things. And like many people who came from China, of course, she had, I remember, beautiful icons and some good quality silver items in her house. Her furniture was old-fashioned, you could say, but her taste was very good in this respect. She was probably already 80 years old when I first met her. I can’t say whether she was an optimist or a pessimist, but she was lively, kept herself busy doing things all the time. She was interested in everything and had a great love for life. She spoke excellent English.

Natalia Novikova. Film actress and Nina’s past friend. From her letter dated 28.7.2021

«I met Nina in the late 90s in Hobart. Shortly before that, I moved to live in Tasmania and was looking for Russian-speaking people to communicate. And now, by the will of fate, Nina appeared before me. I remember very well her funny infectious laugh, bell-bottomed trousers, blouse with a bow and knitted waistcoat. At the age of 76, then she looked very stylish and was full of amazing energy and cheerfulness.

At first, she dealt with me with caution, because I was ‘Soviet’, but after a couple of meetings we were already best friends. Then she once said to me, «Natasha, I don’t feel at all that we have a difference in age." She told me a lot about her family, about her sisters and mother and their fate. She was sure that she was an orphan — once she had a dream, which she interpreted as the news that her whole family had died. She did not know how, but most likely from the repression. Many times, in the past, she and her aunt tried to find them through the Red Cross, but always to no avail.

Nina was an amazing lady who had a huge impact on me — I was 22 years old. Indirectly, she influenced my desire to become an actress (indirectly, because she discouraged me from entering drama school), but could not help but infect me with her love for theatre, music and joy of self-expression.

She lived for other people. I remember once she said to me — «Natasha, I suddenly realized that the most important person is the person who is in front of you at the moment." She also taught drawing — she often saw mothers with children with severe difficulties whom she taught to draw. People brought her fruit, food, but she never took money. I never checked how much money she had in the bank, she said that the Lord always cares about her. I remember she fed a cat called Bitsy, who often dropped in on her. She also fed the mice — leaving them food on the floor every night — so they would not eat her food.

She was very religious, deeply religious. She only ate vegetables, lentils and sometimes fish. She knew how to massage — her aunt owned a massage parlour when they lived in China, where Nina worked in her youth.

Then I went to drama school and moved to another state. We rarely saw each other, only when I came on vacation to Tasmania. I always stayed with her. On one of my visits, she told me about how she accidentally discovered that, it turns out, her mother and sister Alexandra were alive until recently. This is another story. This was a huge blow to her. She was shocked that she had lived her whole life thinking that she was an orphan. She told me that she collected many letters and photographs of her family and gave them to her friend George so that they were not at home — it was so hard for her.

After that, her health began to deteriorate and she lost her infectious laugh, which we all loved so much. I introduced my friends to her, Zulya Kamalova, Eleanor Tucker and others who visited her when I was not in town. She was friends with them, taught them to sing and believe in God. «Nina, how can we pray if we do not believe in God? „Very simply“, she answered „Dear God, in whom I do not believe, etc“

The last time I saw her was in the hospital a few days before her death. She woke up in the hospital in the morning and said: „Lord, am I still here?“ One day, many years later, I happened to meet a 40-year-old woman who was Nina’s student from the school where she taught. When it became clear in the conversation that we both knew Nina, she began to cry and said: „Nina was the only person who believed in me. She influenced my entire subsequent life“ This also applied to me, and I am certain others too. She left you feeling like you were worth something and were special. That’s what our Nina Nikolaevna was like!»

Jeremy Keane, former Nina’s Australian student, friend and colleague, and researcher of her life (born 1970)

«I first met Nina in 1984 at Dominic College where she was my art teacher. There was something special about her, with a kind of eccentricity, a mysteriousness and warmth. She was a very passionate teacher and very popular. When I qualified as a teacher, we felt like colleagues and became very close friends sharing many common things and interests. We had similar sense of humour, some common friends and we both loved art, a liking for individual artists and music, especially piano. We both had similar views of the modern world and we regularly chatted and philosophised about nearly everything. We would talk at the kitchen table for hours. Our conversations were always interesting, often intriguing, and full of exuberance and mirth. Nina took great interest in my teaching, my photography and there was a natural empathy between us. She used to say I saved her life through my praise of her artworks and talents. Of course, this was just kind talk without any foundation. But she was really very talented.

Whether through the care of an animal, the love of friends, or her charitable work Nina was the most thoughtful sincere and generous person I had and to this day have ever met. Life for her was about the people in it, about teaching, justice, church, faith, and above all love. She was an exceptional and beautiful human-being who will be remembered by all those whose life she touched.

Nina’s life was amazing and full of drama. It was incredibly intricate, adventurous, even tragic, yet overall full of love beauty and perseverance. She never lost heart and always maintained a positive outlook on life and sense of humour. She was a wonderful inspiring teacher in every sense of the word and for me the dearest of friends.

To me I would say she was from another world and time. Nina didn’t care about material wealth. She didn’t even have hot water in the kitchen. She wore clothes with flair and style but aside from this she simply had no interest in the acquisition of objects.

This was a woman who grew up in a world where she saw immense wealth such as the Bibikov dacha and mansion in Ekateringburg and then near poverty as the Revolution took greater hold. Consequently, she never took great interest in riches. Rather she took interest in the arts and in the character and soul of people she would encounter. She had immense compassion for others and deeply cared for her friends.

Before I met Nina, I knew practically nothing about Russians. I had acquired some knowledge about the Romanovs and the revolution, but I had no views on Russian culture and history. We were not taught this at school. Thanks to the fact that I became close friends with Nina, this began to change, and gradually I became more and more interested in all things Russian. Since then, I have compiled a library of books on the history and culture of Russia. What I discovered was that I felt a connection with the Russian people. There is so much history, so much adversity overcome, and a deep soul — an indefinable essence.

I discovered how much turmoil she and millions of other Russians had to go through. Nina’s life was not ordinary. She was a rare individual both enigmatic and charming. So special was her life that it deserved to be studied revealed and shared.

When Nina was in hospital and she had little time left to live I visited her daily for probably over a week, sometimes with her friend Diana. Upon visiting her two days prior to her passing I was holding her hand in silence. I felt her squeezing my hand for the first and last time. ‘I feel such love’ she cried.

I was with her in her hospital room when she passed away in the middle of the night. There was another lady who entered the room, arriving late in the evening. When Nina took her last breath, the lady began gently singing some religious hymns in Russian and then crossed Nina’s arms. This was a very moving moment. I will never forget it and will always treasure memories of my now departed friend».

And in conclusion

Each family has its own history, which, I think, everyone will agree, it is desirable to preserve and pass on to the next generation. But it is a pity that many of us don’t do this — do not write down our memoirs during our lifetime or with the help of others. Thus, family history is lost; no tribute is paid to the memory of relatives and our predecessors. And the legacy goes nowhere. The experience gained during life, knowledge and guidance to descendants are not passed on further, and they are taken with them to their graves. And we all will be none the wiser as a result.

Much has been written about the history of Russians in Australia, but there are names of our compatriots who were remarkable in many ways, about whom, unfortunately, we know little today and their names are in most cases forgotten. And it is desirable that they too be remembered and their names not lost into oblivion. And what comes to mind is poem by our renowned poet A. S. Pushkin «What’s in my name for you» (translated from Russian by the article’s writer).

My name, what is it to you?

It will die like the melancholy roar

Of the breaking wave in a distant shore,

Like the sound of the night in a deep forest

On the slip still remembered

It will leave a faint trace, akin

To an imprint on a headstone marking

In a language, lost of meaning.

What’s in the name? Long forgotten

Beset by new and troubled times,

And in your soul, it won’t rekindle

Memories of me pure and gentle.

But on a day of sadness, and in quiet,

Pronounce it with a sense of longing,

Say: the memory of me has not died

There is a heart, where I abide…

Postscript

I thank everyone who helped in the preparation of this article, shared their memories of Nina: — priests G. Morozov and M. Protopopov, Natalia Novikova, and especially Jeremy Keane for the scans of photos from Nina’s photo albums and other information he sent to me, as well as for his efforts to immortalize memory of his closest friend. Of course, thanks also to the film’s director-producer Vladimir Tikhomirov. Also I thank Tamara Kaliberova in Vladivostok for the photograph of Nina, where Nina was depicted with her friends Larissa Andersen and Tamara Jiganova (sister of the author of the famous album «Russians in Shanghai» v. D. Jiganov who, by the way, is buried in the Sydney’s Rookwood Cemetery). This photo is from Larissa’s archives inherited by Tamara.

Readers can share their views on the issues raised in the «comments» section related to the article published on the website of the newspaper «Edinenie» or write to the author of the article at: alexey.ivacheff@gmail.com

Alexey IVACHEFF, Sydney