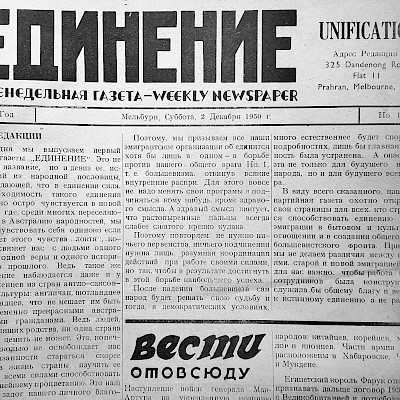

The book by Australian professor Sh. Fitzpatrick "White Russians, Red Peril" caused a lively discussion in the Russian community of Australia. "Unification" in March 2021 published an article by Alexey Ivacheff on this topic. Recently, the editorial office received a letter in which one more opinion of a group of compatriots was expressed. We bring it to your attention.

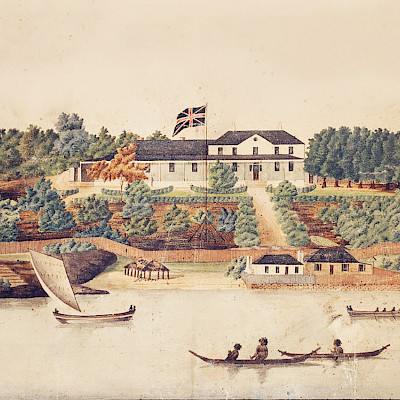

We write to you as Russians from the “European” and “Chinese” waves of immigration in the hope that you will find room for our letter on the pages of “Edinenie”, which for 70 years has been the mirror of Russian community life in Australia. We are concerned about the picture of Russian emigres in the recently published book “White Russians, Red Peril” by Sheila Fitzpatrick, as this concerns us all.

This book has found a negative reaction in our sufficiently extensive circle of friends and acquaintances in the Russian communities of Melbourne and Sydney. It is not our intention to cast aspersions on Professor Fitzpatrick’s academic credentials or start a witch-hunt of sorts: our remarks are a distillation of our own and our friends’ views regarding this particular book. It is not, and does not aspire to be a peer review, but when a published book enters the public domain, it is open to comment and criticism unhindered by the limitations faced by “qualified” peer reviewers. Open public reaction/criticism is just that – sharing with others one’s judgment of the author’s work for what it is, and what it is perceived to be.

The dry, statistical approach in the book leads to misconceptions. misinterpretations and ambiguity, with offensive implications for those who lived through this period and/or their descendants.

The impression conveyed throughout the book is a lack of any empathy with (let alone sympathy for) the White Russians the author subjects to scrutiny – in a word, it comes across as a bleak, rather soulless work. The complacent, statistically oriented, and superficial understanding of the fate of Russian migrants misses the human interest that would have introduced a bit of yeast into the heavy dough of the narrative.

Some of the faults may be caused by the author’s excessive dependence on her researchers, who either have not been/ are not members of the Australian Russian community, or whose contact with it seems very tenuous. There are whole layers of poor research into aspects of the life and activities of the Russian communities, alongside copious but tendentious material on such émigré bodies as the Russian Liberation Army, the NTS, and the Russian Orthodox Church in exile to name just three. The number of paragraphs devoted to a subject does not necessarily guarantee quality.

For us, and many other readers who are Russian Orthodox Christians and churchgoers, questions concerning the Church are a sensitive issue. In the post-revolutionary Russian diaspora, the Russian Orthodox Church was the main rallying point and affirmation of the common lot and inherent allegiance to the faith for most of the dispossessed. This is something that has been sneered at by the “liberal secular intelligentsia” but has proved to be true, nonetheless. The first concern of Russian emigres, wherever they were, was acquiring premises for religious services and later - establishing their very own church buildings. That is a historical fact we would challenge anyone to disprove. Well into the 1950s and to some extent even today, the life of the Russian communities revolved around the Church. Inarguably, in the early years, some did come only to socialize every Sunday in the churchyard for lack of another venue, and not set foot inside to pray. Yet who is to say that some of those who came to the churchyard alone did not, at some later stage, venture inside?

Furthermore, there are some surprising omissions regarding prominent personages in the communities: admittedly, one cannot “embrace the immensity”, but there is legitimate cause for complaint about factual errors concerning some of the people who do rate a mention. Taken individually, those errors may seem insignificant, albeit annoying to their living relatives who could have supplied first-hand information; however, all such small mistakes in aggregate cannot but cast doubt on the credibility of the whole book.

If Professor Fitzpatrick intends to publish a sequel or an amended edition, one hopes that she will be more careful in checking her work, rather than depending too much on her subordinates.

It is a pity that a book that might have been a milestone work in the historical record of the Russian post-revolutionary diaspora has turned out to be, as Shakespeare put it, is “much ado about nothing”…

Yours respectfully,

Helena Kojevnikov (nee Berdnikova) granddaughter of the first technical editor of “Edinenie” V.P. Komarov, stepdaughter of his successor, Yu.K. Amosov; (Melbourne - London)

Tatiana Stemmer (nee Amosova) granddaughter of the first technical editor of “Edinenie” V.P. Komarov, daughter of his successor, Yu.K. Amosov; (Melbourne)

Alexander Vassilieff, former Foundation President and Chairman of the Russian Ethnic Community Council N.S.W. (Sydney)

18 July 2021