There are some special places in any contemporary cities all over the word. These places, connecting the Past and the Present, give us an opportunity to imagine how the nearest Future will be like. One of the places of this sort is the Queensland Museum in Brisbane. Here I learned about the amazing fate of Afanasy Bobileff’s family, or rather, about the fate of the whole generation of Russian people who went through the revolution, the civil war and immigration.

Last year during the Russian Heritage Week which is a part of Australian Heritage Festival, we had a unique opportunity to join Behind- the- Scenes Curator Tour in the Queensland Museum and see artefacts of the Museum’s Russian collection. The artefacts are related to the history of the Russians, who by the will of fate found themselves in distant Australia a hundred years ago.

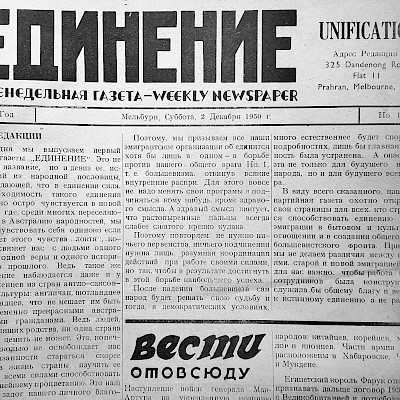

Among the many items at the exhibition one certain artefact attracted my attention. It was an old men's winter drape coat, lined with beaver lamb. As it turned out, the Museum's library held a copy of a book called “Anna's Story. A Russian Odyssey” which was written by Constance Mellish, the grand-daughter of Afanasy Bobileff, the owner of the coat. I have read this book and would like to invite the readers of “Unification” on a journey through its pages.

The book begins with a dialogue between Constance and her mother Anna. Constance finds the story of the Bobileffs remarkable and asks Anna to tell the story of her life in detail in order to write a family saga for the children, the grand-children and anyone who is interested in Russian immigration at the beginning of the 20-th century.

The heroine of the book, Anna Afanasyevna Bobileff, was born on December 5, 1913, in the Siberian village of Durovka, near the town of Bogotol, the administrative center of the Bogotol volost of the former Mariinsky district of the Tomsk province. Her father Afanasy Feodorovitch Bobileff was the District Commissioner. He was from the city of Smolensk, from a wealthy peasant family who had moved to Siberia, where at that time the settlers were given plots of land in full ownership. Afanasy Feodorovitch was graduated from the St. Petersburg Theological Seminary. Because he was from a simple family this was the only opportunity to receive a classical education. Afanasy did not become a Russian Orthodox priest, because he did not agree completely with some of the Church doctrines and could not accept the contrast between the wealth of the church and the poverty of people. Being a man of culture and education, fluent in three languages, Bobileff somehow sensed the collapse of the Russian Empire and oncoming tragical events. He left Russia at the age of 29, a week after Easter in order to find a new home for his family in another country.

Shortly after Afanasy's departure, his wife Maria Timofeevna learnt of her pregnancy. This child was Anna. It is necessary to tell you a little about Maria Timofeevna. She was born in the rich estate of a retired general of the tsarist army near the city of Vitebsk. Her father was one of the five illegitimate children of the general from a young beautiful Polish woman. The general could not legitimize their union, as he was married to a Russian aristocrat who permanently lived in Paris. Which, however, did not prevent him from tenderly loving the young woman who became his real wife and arranging the fate of their common children.

All the sons got educated and found their rightful place in life. Everyone except the youngest Timofey, handsome and reveller. Timofey was not interested in anything but gambling, unrestrained galloping through the fields and flirting with local young ladies. But it was hard to resist his appearance and reckless prowess. Polina, a girl from a wealthy Moscow family, could not resist him either. They got married in a 16th-century church in Vitebsk. Six children were born from this marriage: three sons and three daughters, the youngest of the daughters was Maria Timofeevna.

This marriage was not a happy one. At first, the family was supported by the general, Timofey's father, but after his death the estate was sold and the money was sent to the lawful wife of the late general. Now the well-being of the family was completely dependent on the help from Polina's parents. Instead of taking part in the management of the family property, Timofey continued to play, get drunk and seduce peasant girls. Scandals and quarrels with tears and curses occurred every day. There is nothing surprising in the fact that, having reached the age of fifteen, Maria Timofeevna had already been engaged to a wealthy man and intended to leave her parents' house, which had become disgusting to her. But then true love entered her life and suddenly changed these plans.

Maria was visiting her uncle's wealthy and hospitable home in St. Petersburg when she met Afanasy Bobileff, an educated twenty-five-year-old young man just starting his career. Probably it was love at first sight. They got married in the same church in Vitebsk, where Maria's parents had once been married. During the wedding, the rejected bridegroom burst into the church and cursing the young, fired his revolver. Athanasy covered the bride with his body, and Maria’s relatives, who arrived in time, disarmed and tied the jealous man. After four happy years of family life, Athanasy decided to find a new home for his family outside the Russian Empire.

Afanasy Bobileff was travelling with a friend, a young man living nearby in the village of Durovka. Anna was too little to memorize his name. The friends took a train from Bogotol to Krasnoyarsk and from Krasnoyarsk to Irkutsk. In Irkutsk they took another train to Chita, and after that the young men got to Vladivostok by the legendary Chinese Eastern Railroad, going via Manchuria. Built in 1897 - 1903 as a southern branch of Trans-Siberian Railway, the Chinese Eastern Railroad belonged to the Russian Imperia and was run by Russian staff.

The friends stayed in Vladivostok for three days before boarding a ship bound for Alaska, to the city of Sitka*, the former Russian capital of Alaska. The Russian Empire sold Alaska to America for half a cent per hundred square meters on October 18, 1867 in Sitka, which at that time was called Novo-Arkhangelsk.

In 1913 when the friends arrived, Alaska still was considered to be a land of opportunity, even though the gold rush was almost finished. The country was rich in fish, timber, coal, copper and animals. It was said one could walk across the Bering Strait, the narrow waterway, separating Alaska from Russia on the backs of the salmon. American canneries were in full production, catching and canning salmon. The two young Russians worked for three weeks in one of these canneries. This was enough to understand that the work was hard and unpromising, and there was no question of opening a business, the monopoly on managing the economy in Alaska belonged to large American financiers such as Morgan.

Traveling across Alaska by boat and dog sled, Afanasy and his friend were fascinated by the harsh beauty of the country. But Alaska was not the place they were looking for their families. Alaska had no railways, but it was full of saloons and brothels. The indigenous people inhabiting Alaska were discriminated, and the white population seemed not to be interested in anything other than drinking and gambling.

The young men found Alaska to be too Godless and rough, the last frontier. The twenty-three years old friend of Afanasy Bobileff was already homesick for his parents and sister and the Russian way of life. He decided to return home on a ship going to Russia. Afanasy Feodorovitch gave him a parcel of gifts, including Eskimo crafted bags and fur boots to be delivered to his wife Maria, back in Siberia. Bobileff decided to leave Alaska for Canada, but his plan was not destined to be fulfilled.

As soon as his friend was gone, another ship came in the bay of Sitka. Afanasy recognized a man he knew on the deck, a crew member, who hailed him and invited him on board. As it turned out, the ship St. Albans was going to Australia, where gold, was said to be found in Western Victoria. Afanasy was given a job – he became a Captain’s steward. They sailed the following morning at first light, travelling south-west through the Pacific Ocean.

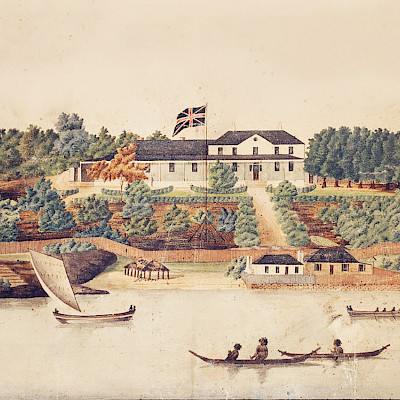

We know the exact date of Afanasy Bobileff’s arrival in Queensland – the first of January 1914**. Soon Bobileff found himself in Sydney. From Sydney he caught a train to Melbourne and then a horse drawn coach to the goldfields of Western Victoria and got disappointed by a brash country: there were no shovelful of gold. But traveling around Australia and getting to the North of Queensland, the wanderer found a real treasure - the incredible beauty and diversity of the Tropics. He also liked the way of life that prevailed in this English colony, especially since he considered English law to be the best in the world. Athanasy realized that he had finally found a new home for his family, so different from Siberia. And if you change your life, it's better to start with a renewal in everything! How could he know that his plans and decisions would be disrupted when England declared war against Germany in 1914? Being an English ally, Australia too was at war.

He couldn’t imagine himself to be sent to the mines on Mount Morgan near Rockhampton as a non-British resident. He spent nearly four years in there, mining copper for the army. Carefully made plans and happy dreams crashed into harsh reality - the 20th century began to grind human lives around the world. Australia paid a terrible price for its participation in this war: 62,000 soldiers and officers were killed, and 156,000 were wounded, gassed or captured. For the country with a population of five million people, this was a huge, terrible, irreparable loss. A wound that still bleeds …

When World War I ended in November 1918, Afanasy Feodorovitch was still working at one of the many mines on Mount Morgan. Found himself in the multicultural group of immigrants from Russia, Italy, Yugoslavia, Poland and Greece, Bobilef enjoyed companionship of his co-workers, having a spiritual rest from his lonely wanderings. Among the other Russians, there was a member of the newly formed Australian Communist Party, mentioned in Constance Mellish’s book as Basil T. Despite their differences of opinion, Basil and Afanasy respected each other and even became friends. In 1919 the Communist Party was under deep suspicion in Australia and Basil T. was deported back to the Soviet Russia. This person would play an important role in Afanasy’s life.

Afanasy Feodorovitch was in turmoil: newspaper reports of the Russian Revolution, and any general news of Russia were scant and far between. The murderer of The Russian Royal Family filled him with horror. He didn’t know if his family was dead or alive. In the chaos of the Revolution no mail was possible.

He decided he must return home to his family. He applied for naturalisation papers in Brisbane, to become an Australian citizen, but it was delayed by authorities. He had reasoned this might afford him some protection from Bolshevik authorities in Russa. But Afanasy had no time to waste, he could no longer live without knowing what happened to his family. Having bought a lot of presents, including a new Singer sewing machine for his beloved wife Maria, Bobileff left Australia in April of 1919 on board of an English ship, heading to Europe. He got a job of a steward on board. This three-month journey via Singapore, Rangoon and the other major seaports was supposed to be ended in Constantinople (contemporary Istanbul) on the Mediterranean Sea.

Afanasy’s good manners and perfect English and also his ability to play chess and bridge brilliantly, helped him to become the captain's favorite and personal steward. There was a game of bridge for money in the captain’s cabin almost every evening with the participation of the captain himself, two first-class passengers and the steward Bobileff. This allowed Afanasy, thanks to his skill and luck, to accumulate a significant amount.

Obsessed with the desire to beg forgiveness from his wife for a long absence, he bought a bag of rubies from a jeweller in Rangoon for his beloved one. By a fatal accident, this purchase was witnessed by a first-class passenger, Russian by nationality, who was also heading to Russia from Hong Kong in search of her relatives. Anticipating trouble Afanasy hid the rubies and the gold coins inside the long tunnelled out bars of Sunlight soap in his luggage.

Having disembarked in Istanbul after a warm farewell to the captain, Afanasy deposited half of his money in the Bank of England, before buying passage on a smaller ship to Odessa. He left carrying paper money, English five-pound notes, and Russian roubles, issued by Kerensky and Trotsky. He also carried an amount of Russian gold coins which he planned to declare if need be. The capital stock was also in his luggage, safely hidden in bars of Sunlight brand soap.

Bobileff bought a ticket for a small boat bound for Odessa. Unfortunately, on the same ship was that very Russian a first-class passenger who became an unwitting witness to Afanasy's purchase of rubies in Rangoon. During the inspection at the customs of Odessa, nothing was found in the luggage of Afanasy Feodorovitch that was not subject to import into the country. Three hundred royal chervonets were confiscated, and their former owner, who was beside his feet with joy, received permission to leave the customs and set foot on his native land. But it was not there! The same Russian named Katerina, trying to avoid a search and confiscation of her own treasures, accused Afanasy of smuggling gold and rubies. It did not help her: the gold coins hidden among the clothes in her luggage were immediately confiscated. Afanasy Feodorovitch Bobileff was arrested and thrown into one of the Odessa’s prisons.

It is very hard to know which prison he was taken to. It was the time of so-called Red Terror in Odessa from April to October in 1919, when law and order was ruling by Che-ka: The Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution. It is unknown what sort of position Basil T. who once worked with Afanasy in Mount Morgan Mines, took in The Province Extraordinary Commission. He, obviously, had enough of power to release Bobileff from prison, when he noticed his name on the hit list.

Afanasy Feodorovitch found himself in the country which was in the complete chaos of revolution and where the Soviet power was finally established only in 1920. There were no trains, no services. The Red Army was still fighting The White Army on several fronts. There also were a Peasant Army in the fry and even a Green Army up in the North. They were all running around and fighting each other. Afanasy realized, he wouldn’t get a hundred kilometres without being shot by one or the other, so he returned to Constantinople and after that, to Australia.

After his desperate attempt to reunite his family Bobileff remained in Australia, writing letters monthly to his beloved wife Maria Timofeevna to Siberia, until finally one such letter did reach its destination and he got the return mail in 1922.

What was going on the other side of the world in faraway Siberia after Afanasy’s departure? His wife Maria Timofeevna, her two baby daughters Lucy and Anna, Agarfeya her mother-in-law and Irina her sister-in-law were living in the same house in the village of Durovka. Afanasy Feodorovitch had organised before he left in 1913, seven good men, political prisoners, to be assigned to his farm to work. These men slept in the barn with the cattle, but had their meals with the family. This work force was later supplemented with prisoners of war – Austrians and Czechoslovakians. Having free and conscientious workers, the Bobileffs comfortably survived wartime. The relatively calm and prosperous life of the family ended in the summer of 1918.

The first disaster to strike this household of women was the disappearance in late July of their seven men servants, who worked the farm. One night they all disappeared, taking with them much food from the cellar. One week later a detachment of the Red Army came to the village of Durovka. They confiscated most of the livestock and grain from the farmers. The Red Army men also burnt down the village church. That was the last straw for the inhabitants of the village. Two days later, six village families embarked in a straggly cavalcade to set up a camp in the safety of the forest. For old men, fourteen women, eleven children – twenty- nine souls in all. They pushed carts, carrying food, tools and everything their needed for everyday life. When they had gone about five kilometres from the village of Durovka, they were lucky to find a small clearing, surrounded by birch trees with a creek nearby. They build shelters, where they stayed until late September, when the cold weather pushed them to return to the village.

The Bobileff’s family survived the civil war which came to the end in Siberia only in January 1920, when the Red Army, having defeated the Kolchak’s Army, took the city of Irkutsk. They survived starvation and an Asian cholera epidemic, which took thousands of lives in the winter of 1919. When on the night of 13 to 14 December 1919 the 27-th Division of the 5-th Army entered the city of Novonikolayevck, they found a lot of sick people in there. Streets were piled high with bodies. Kolchak’s retreating army left thousands of hungry sick soldiers behind. They scattered throughout villages, spreading the disease. But the disease passed Bobileff’s house by. Anna even started her school studies. Unfortunately, the school was shut down in a few months: a lot of children died and survivors were very weak due to starvation and unable to go to school.

Maria Timofeevna hadn’t got any news from her husband for six long hard years. She got the strength to survive such crucial life changes from her children, her optimistic way to live and continuing belief in God. She spent hours knelling before icons, praying for her husband to return home. The letter from Afanasy Feodorovitch came on Easter in 1922 and was read to pieces.

By that time Bobileff had already bought some land in Innisfail, where he was waiting for his family to come. But it was absolutely impossible to transfer any money to Russia at that time. Afanasy advised his wife to sell out the property and all their belongings and use the money to get to Harbin, where he had already deposited some money for his family in the Bank of England.

The Bobileff’s family didn’t have much to sell. The farm now belonged to the State, but there were Afanasy Feodorovitch’s books, some furniture and rugs, some bedding. It took more than one year to obtain the necessary permits and visas, fortunately the Bolsheviks opened the borders for people, who wanted to leave the country in 1922. All the necessary documents were obtained only by the summer of 1923.

Maria with the children set off in August 1923 in a cattle train from Bogotol, moving eastward across Siberia to China on the Trans-Siberian Railway line. There were few proper trains left, most had been destroyed during the war. Maria and the two little girls had to spend five days and nights on the dirty floor of the compartment, stealthily eat at night in order not to show fellow travellers their meagre provisions and sleep in turns, protecting the luggage, before the train pulled into the large town of Irkutsk. Afanasy Fedorovitch had good friends in Irkutsk - a wealthy family who also wanted to immigrate. He advised Maria Timofeevna to address them in his last telegram, which she received just before her departure. The exhausted woman with two small children walked, currying the heavy staff

to the other end of the city in order to find an empty house abandoned by the inhabitants. Desperate, with the last of their strength, the family returned back to the station to spend another week there, waiting for the next train to Chita. They slept on the floor in a corner of the station tearoom, where a tender-hearted barmaid sheltered them.

On the seventh day, they managed to take places on a bench in the train, going to Chita. They were incredibly lucky, as the train was moving very slowly, stopping at every small village. The journey, which in the old days would have taken two days, took Maria Timofeevna with the children two weeks. But it was nothing compare to what was awaiting them in Chita. They were to spend two months in Chita to obtain a final permit to leave the country. They got their papers only when Maria lost her last hope and the girls were crying hungry. Maria Timofeevna spent all her money for food and accommodation. She had only her last reserve left – the gold coins, hidden in her shoe – for the tickets to leave Chita for Harbin. It was barely enough for buying three tickets in First Class, because children were not allowed to travel in Second Class. The legendary Trans-Siberian Express took the Bobileffs to Manchuria, to the rich city of Harbin, to a new life…

The new life began as soon as the Bobileffs arrived at Harbin Central Station where Afanasy’s friend, a Colonel of the Tsar’s army, who left Russia in 1920 with the defeated White Guards of Admiral Kolchak, was waiting for them. Constance Mellish gave the name of this person, but I am not sure of the correct spelling and do not want to mislead readers. I only say that he was a man of great culture, spoke six languages, including Chinese and now earned a meagre living as an interpreter for Customs for the Port of Harbin. This person helped Maria Timofeevna to obtain the money, sent by her husband to the Bank of England in Harbin. She and the girls would stay in a small flat of Afanasy’s friend for a week until the money was released.

As soon as the opportunity arose, Maria Timofeevna rented a small room in the same large block of apartments. They lived in there for a month before leaving for Dalian. From there they crossed the Yellow Sea aboard a small Chinese ship to reach Incheon in Korea. This two-day voyage became a real nightmare for the family: they had to endure all the agony of seasickness. In Incheon they immediately take a train to Pusan, from where they reached Nagasaki by sea. Fortunately, this voyage was not as tiring as the previous one: the travellers managed to adapt to the pitching and no longer suffered from seasickness.

Having arrived in Nagasaki, they had a two-weeks break in a good hotel, residing in comfort, until their boat, the SS Yohumo Maru left for Townsville in Australia. The boat trip on the Japanese vessel took almost a month, as they took stops at Shanghai, Hong Kong, Singapore, Batavia (Jakarta). Anna recalled it was not a happy time. Their Second-Class cabin was very small, the food was bad, the crew were rude, arrogant and uncaring. They were happy to reach Thursday Island, a stopping point for vessels, coming from overseas. At the Customs House they were issued with a receipt for their passport papers – Mrs Bobileff and two children Passport № 3780, issued to Maria Timofeinova by the Government of Harbin.

The ship sailed down the east coast of Australia, passed the Great Barrier Reef and four days later reached Townsville on the mainland on a January morning in 1924. Afanasy Feodorovitch was not there to meet them, which was a great disappointment. There was no railway built as yet in those days in the Far North. It was the rainy cyclone season, and there was no boat either available from Innisfail. Bobileff organised a Russian friend, a journalist who lived and worked in Townsville to meet his family.

The small Russian community of Townsville welcomed them with generous hospitality. There were dinners and afternoon teas and offers for accommodation for ten days until the next costal steamer appeared to take them to Mourilyan Harbour. They made their way up the coast to Mourilyan Harbour near the town of Innisfail, where Afanasy Feodorovitch was waiting for them on the wharf. The family got reunited, the tearing six months journey from Siberia to Australia was over. This story of loss and gain, despair and faith had a happy ending.

The family settled in East Innisfail on a fresh water creek in the house of wood with verandas, built by Afanasy. Maria Timofeevna straight away put in a large vegetable garden and purchased chicken, ducks and a milking cow. She even got rid of a large fresh water crocodile, stealing the ducklings from the backyard, by beating it on the head with her broom. Anna and Lucy very quickly became assimilated to their new surroundings and went to school.

After some time, the family had moved from East Innisfail to Lily Street in the centre of the town, where Afanasy had purchased an old house on a large block of land. He rented out the house and, on the land, alongside built a boarding house. It was two storeyed, the family lived upstairs, while for the boarders there were four rooms downstairs. At week-ends the place was always full. Farm workers, cane cutters, cedar timber getters all came to town on Saturday night to spend their hard-earned money. Over the next few years Afanasy Feodorovitch Bobileff sponsored twenty-nine White Russian families with the Australian Government to find their new home. On first arrival they stayed at Bobileff’s place, before moving south to the big cities, usually Sydney or Melbourne.

Afanasy and Maria got for two children more in Innisfail: a son Peter and a daughter Mary. Lucy and Anna grew up. Anna dot married to Walter Shapowloff. The Bobileffs moved to Brisbane in the mid-1930s. Their family tree was growing and getting new branches, life was going by. And only one thing has remained unchanged – the love story which survived the war, the revolution, the separation and a great distance. Afanasy Feodorovitch and Maria Timofeevna are still together – resting in peace in Bulimba Cemetery ***. This is the story I learned from the old coat in the Brisbane Museum. It is really amazing, how much museum artefacts can tell you, especially if they are held with caring hands…

*In the article “Connecting People and Time” dated 06/17/2019, I wrote that Afanasy Bobileff came to Australia from Japan, based on information provided by the Queensland Museum staff. According to Constance Mellish, her grandfather came to Australia from Alaska, which seems to be more logical.

**Register of Immigrants Brisbane 1885 to 1917, page 120 – item ID 18611 – Reg IMM/136. Microfilm: Z3987.

***Find a Grave, database and images: memorial page for Afanasy Bobileff (1884-1956), Grave Memorial no. 183555957, citing Balmoral Cemetery, Brisbane, Brisbane City, Queensland, Australia.

Nataliya Samokhina

Brisbane

Constance Mellish "Anna's Story. A Russian Odyssey".

The book was published in 2003 and has already become a bibliographic rarity. You can read it in the reading room of the National Library of Australia.